Explore the meaning and significance of vernacular architecture in modern India. Learn about its sustainability, cultural preservation, climate adaptability, challenges, and how integrating traditional practices with modern design can create eco-friendly, regionally sensitive solutions for today’s architectural needs.

Vernacular architecture represents a vital component of contemporary discourse on sustainable design and cultural preservation. Rooted in the unique climatic, cultural, and geographical contexts of specific regions, vernacular architecture embodies centuries of traditional knowledge and craftsmanship. It reflects an inherent understanding of local materials and building techniques, honed over generations to create structures that are not only functional but also harmonious with their environment. In a country as diverse as India, where climatic variations and cultural practices are manifold, vernacular architecture serves as a practical blueprint for addressing modern construction challenges.

As the world grapples with the pressing need for sustainable development, the principles of vernacular architecture offer valuable insights into resource-efficient practices that prioritize local materials and community involvement.

This article delves into the origins and significance of vernacular architecture in the Indian context, highlighting its relevance in today’s architectural landscape.

Table of Content:

1. What is Vernacular Architecture?

Vernacular architecture refers to structures that emerge organically from local communities, built by individuals who often lack formal architectural training. These constructions rely on techniques and knowledge that have been passed down through generations, often through oral traditions. By harnessing locally available materials and engaging community members in the construction process, vernacular architecture reflects a deep understanding of the region’s climate, cultural practices, and social dynamics.

This architectural approach stands in stark contrast to contemporary trends characterized by standardized designs and industrial replication. Instead, vernacular architecture embodies a responsive relationship with its environment, effectively addressing the unique social and natural needs of the community it serves.

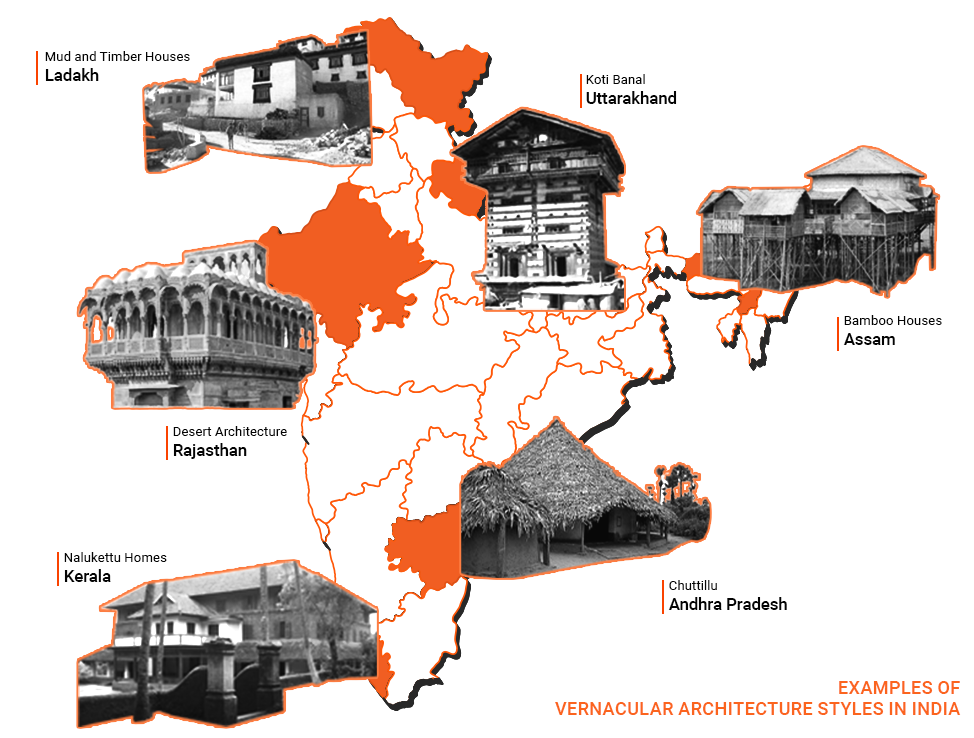

In India, the rich network of diverse cultures and traditions gives rise to a multitude of regional variations in vernacular architecture. Each regional style demonstrates a unique adaptation to local conditions, showcasing the ingenuity and resourcefulness of its builders. From the mud houses of Rajasthan to the bamboo structures of Assam, vernacular architecture in India is a testament to the country’s varied climatic zones and cultural heritage.

2. The Importance of Vernacular Architecture in Modern India

As India continues to urbanize and confront various environmental challenges, incorporating or simply borrowing from the underlying philosophy of vernacular architecture offers a more sustainable approach to conventional modern construction methods. It effectively addresses ecological conservation, cultural heritage preservation, and climate adaptability.

a. Sustainability and Resource Efficiency

Vernacular architecture emphasizes sustainability by utilizing locally sourced materials such as mud, stone, bamboo, and timber. This approach significantly reduces transportation costs and minimizes the environmental footprint often associated with modern construction materials like concrete and steel. Traditional materials are generally renewable and have a lower environmental impact. For instance, homes in Rajasthan, constructed with mud or stone, exhibit high thermal capacity, allowing them to regulate internal temperatures effectively without relying on artificial heating or cooling systems. Similarly, houses in Kerala, built with timber and clay, are designed for optimal ventilation, which reduces the need for air conditioning. By leveraging local resources and traditional technologies, vernacular architecture presents an environmentally sustainable and cost-effective solution in the long term.

b. Cultural Preservation

Vernacular architecture serves as a testament to a region’s rich cultural heritage, encapsulating centuries of traditional practices and moral values. Preserving indigenous construction techniques is vital for conserving India’s cultural diversity. For example, the architectural layout in South India often follows Vaastu Shastra principles, which govern spatial arrangements in construction. Integrating these concepts into modern architectural practices not only maintains cultural significance but also fosters a connection for future generations to their built environment.

c. Climate Adaptability and Resilience

Vernacular structures are inherently designed to withstand the rigors of local climatic conditions. In flood-prone regions like Assam, especially in its riverine area’s houses are constructed from bamboo, providing resilience against inundation, while in the arid desert climate of Rajasthan, thick mud walls help retain cooler temperatures. These adaptive strategies, developed over generations, remain highly relevant in contemporary architecture, particularly as the effects of climate change intensify. Designing buildings that harmonize with their environmental context is essential for fostering resilient communities capable of withstanding natural disasters.

3. Challenges of vernacular architecture

Despite its merits, vernacular architecture in modern India encounters several challenges. Traditional designs may appear less suitable for today’s rapidly urbanizing society, and there is a shortage of skilled artisans trained in vernacular techniques due to the contemporary emphasis on modern construction methods.

To address these challenges, it is imperative for governments and other stakeholders to invest in education and training programs that impart knowledge of both traditional and modern construction techniques. By synthesizing these approaches, innovative and sustainable architectural designs can emerge. As awareness of climate change grows and the demand for eco-friendly construction rises, vernacular architecture is likely to gain increased recognition and relevance.

As cities and countries modernize to meet global construction standards, vernacular architecture provides a path that acknowledges global trends while preserving regional identity and embracing sustainable development. By revitalizing these strategies, architects can ensure that the future of Indian architecture remains as rich and robust as its history.

4. Morphogenesis’ Projects in Focus

With sustainability at the core of Morphogenesis’s design philosophy, each project emphasizes sustainable practices uniquely—whether through the application of the Venturi effect for natural cooling or the use of locally sourced materials in construction.

Below are three projects that showcase Morphogenesis’s dedication to sustainability, drawing inspiration from local traditions and vernacular architectural practices specific to each region:

a. Pearl Academy, Jaipur

Image Courtesy: Andre Fanthome

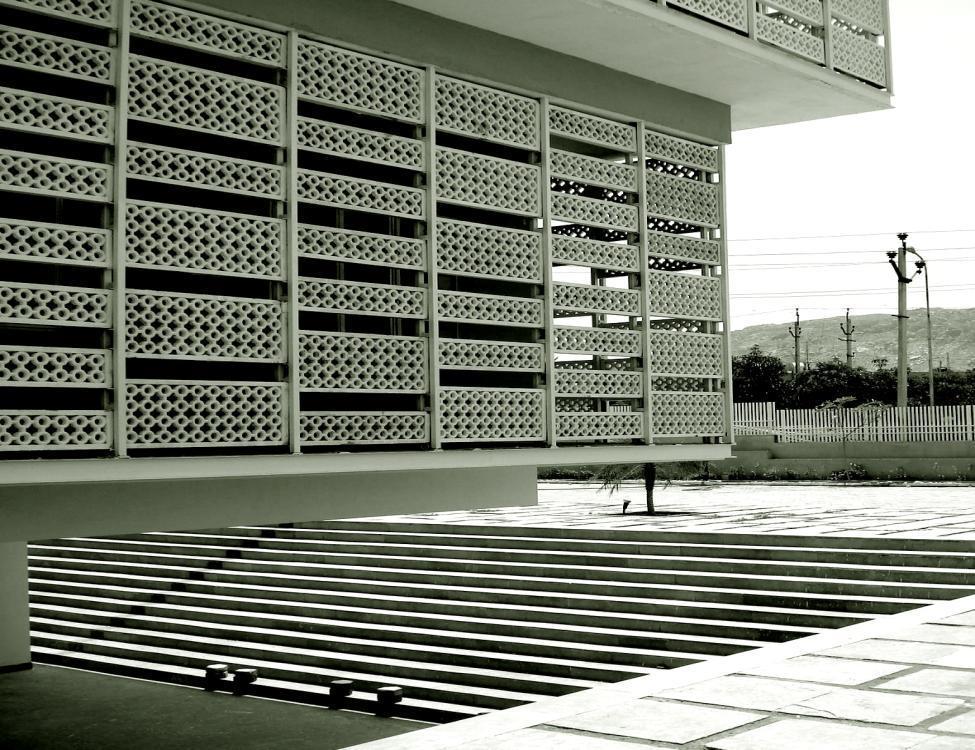

Recipient of India’s first World Architecture Festival (WAF) Award for ‘Best Learning Building’ in Barcelona, The Pearl Academy project in Jaipur exemplifies a commitment to creating an environmentally responsive habitat that harmoniously blends traditional and contemporary architectural practices. This innovative institute is designed with a deep understanding of Jaipur’s hot and arid climate, utilizing vernacular architecture principles to address local design challenges.

At the heart of the academy’s design is a series of interactive spaces that encourage collaboration among a creative student body. These multifunctional zones seamlessly integrate indoor and outdoor environments, promoting a fluid, continuous experience throughout the campus. While the building presents a compact, rectilinear exterior, the thoughtfully designed internal courtyards foster a sense of openness and perpetual movement.

Image Courtesy: Edmund Sumner

The architecture of Pearl Academy draws heavily on modern adaptations of traditional Indo-Islamic elements, employing passive cooling strategies that are characteristic of Rajasthan’s desert region. Notable features include self-shading courtyards, water bodies, baolis (stepwells), and jaalis (perforated screens), which collectively enhance thermal comfort and environmental performance.

A distinctive double-skin façade, composed of jaalis, serves as a thermal buffer, reducing direct heat gain through carefully articulated fenestrations. This design functions as a triad of filters—air, light, and privacy—allowing for a comfortable interior atmosphere while respecting the local context. Moreover, low-cost, traditionally inspired methods of roof insulation further mitigate heat absorption. Inverted matkas (earthen pots) are strategically placed on the roof, with gaps filled with sand and broken bricks, then covered with a thin layer of concrete, exemplifying the resourcefulness of vernacular building techniques.

Image Courtesy: Morphogenesis

The Pearl Academy stands as a testament to inclusive architecture that is not only socio-culturally relevant but also inspired by local heritage. It successfully positions itself within the contemporary architectural landscape while honoring traditional practices. This innovative approach earned Pearl, highlighting its significant contribution to the field of vernacular architecture.

b. Kumarakom Resort, Kerala

Image Courtesy: Morphogenesis

The Kumarakom Resort project exemplifies how modern sustainable architecture can continue Kerala’s rich architectural legacy while embracing cutting-edge design principles. Inspired by the Nalukettu, a traditional Kerala architectural style characterized by a courtyard surrounded by four blocks with sloping roofs, this project integrates these vernacular elements with innovative adaptations. The result is a sophisticated yet contextual resort that creates a seamless dialogue between traditional design principles and environmental responsiveness.

In designing this resort, Morphogenesis sustainable architects went beyond aesthetic replication of the Nalukettu; it applies local materials, passive cooling strategies, and natural ventilation methods to ensure the structure operates in harmony with its surroundings.

The hyperbolic roof design, inspired by the spread of a tree canopy, serves both as a shading device and a means to enhance thermal circulation. By harnessing the Venturi effect – where wind accelerates as it passes through narrow spaces – the resort achieves natural cooling without reliance on energy-intensive systems.

Image Courtesy: Morphogenesis

The villas’ orientation and placement are strategically designed to capture Kerala’s cooling westerly winds, promoting airflow across the site to maintain a comfortable indoor climate year-round. Retractable, perforated cantilevers on the roofs allow for adjustments based on weather conditions, thus blurring the boundary between indoor and outdoor spaces and providing guests with an immersive, climate-responsive experience. This adaptability respects the regional climate’s nuances while allowing the resort to operate with minimal environmental impact.

In this project, Morphogenesis has crafted an environment that is as ecologically sensitive as it is luxurious. By fusing local heritage with advanced architectural strategies, the Kumarakom Resort not only embodies Kerala’s cultural identity but also sets a precedent for sustainable luxury in tropical environments.

c. Lodhsi Community for Forest Essentials, Uttarakhand

Image Courtesy: Andre Fanthome

Morphogenesis’s design for the Lodhsi Community for Forest Essentials epitomizes a modern sustainable approach deeply rooted in the region’s vernacular architecture. Situated along the Ganges in the Himalayan foothills, the facility is inspired by the traditional Garhwali kholi—a form known for its practicality in the region’s climate and landscape.

By reinterpreting this form, Morphogenesis has created a facility that supports a production environment for an Ayurvedic skincare brand, integrating local materials, passive design strategies, and community-driven construction.

The building’s structure is rectilinear and oriented along the East-West axis, with a central entryway dividing the facility. This arrangement optimizes natural airflow while organizing spaces based on temperature requirements—cooler processing areas for herb grinding and storage are placed on the ground floor, while preparation areas, which generate more heat, are on the upper floor.

Image Courtesy: Andre Fanthome

The North-South oriented butterfly roof draws from local roofing traditions while also maximizing ventilation by capturing the Northeast and Southeast winds, with large operable windows allowing for a naturally daylit and well-ventilated interior. The clerestory windows reinforce Bernoulli’s principle, moderating indoor temperatures without mechanical systems.

The design approach balances innovation with sustainability. A high thermal mass façade, achieved through materials like local stone, brick cavity walls, and double glazing, reduces thermal gain and minimizes energy use. With an Energy Performance Index of 35 kWh/m²/year and a solar roof that generates 50 kWp, the facility operates as an energy-positive structure, supplying surplus energy back to the state grid.

Image Courtesy: Andre Fanthome

Further sustainable measures include site-specific rainwater harvesting, optimized for local needs, and comprehensive material repurposing—waste materials like rafters, purlins, and stone chisels are creatively integrated as lighting fixtures, door handles, and more. This net-zero approach to energy, water, and waste, along with significant community engagement through local labor and materials, has led to a facility that not only supports Forest Essentials but enriches the local economy and cultural fabric.

In essence, these project reflect Morphogenesis’s commitment to building resilient structures that resonate with their environment and community. Contemporary, sustainable manufacturing space that stands as epitome of modern vernacular architecture, built by the locals, for the locals, and with a global vision of sustainable development.

5. Integrating Vernacular Architecture into Modern Projects

Approaches and styles of vernacular architecture are often associated with rural life, but they also have a place in modern cities. Many Indian architects have incorporated traditional building styles with modern technology, creating what is known as modern vernacular architecture. This approach combines the features of regional vernacular architecture, such as sustainability and cultural aspects, with modern technologies and comforts.

a. Residential Projects

There is a growing trend among homeowners to build modern vernacular houses using locally sourced construction materials and finishes, along with the latest amenities. Most house designs incorporate natural lighting, ventilation, and sustainable materials like bamboo, mud, and recycled timber.

These architects aim to blend traditional architectural principles with contemporary design to create energy-efficient homes that harmonize with their natural surroundings. Such homes are popular in regions where climate adaptability and sustainability are essential for comfort.

b. Commercial Projects

The principles of vernacular architecture are also relevant to commercial buildings. Current business complexes, corporate offices, hotels, and similar establishments focus on sustainability using local materials and energy-efficient construction methods.

For instance, traditional courtyard designs in commercial properties can significantly reduce energy consumption by incorporating natural ventilation, stone, and timber in construction. Additionally, using vernacular aesthetics in public spaces to create unique environments that reflect the cultural identity of a specific region can enhance commercial properties for local and international clients.

Learn more: The Morphogenesis approach to sustainable architecture

6. Vernacular Architecture Styles from India

a. Nalukettu, Kerala

The Nalukettu homes, a traditional architectural style from Kerala, derive their name from two Malayalam words: ‘Nalu,’ meaning four, and ‘kettu,’ meaning built-up sides. As the name suggests, these homes are characterized by their quadrangular layout, with four sides enclosing a central courtyard. Typically, single-level structures, Nalukettu homes are not only spacious but also thoughtfully designed to suit the climatic conditions of the region.

A key feature of these homes is the high-sloped roof, which efficiently channels rainwater during Kerala’s heavy monsoon seasons. At the heart of the house is the Nalukettu—the central courtyard—which serves as a natural ventilation system, allowing air to circulate freely while also admitting sunlight. This design helps maintain a comfortable indoor climate, even in the humid tropical weather.

The construction materials, including laterite stone and timber, are locally sourced, further enhancing the harmony between the building and its environment. These natural materials not only ensure that the structures blend seamlessly into their surroundings but also contribute to their durability and sustainability.

b. Bamboo Houses, Assam

In regions prone to heavy rainfall and earthquakes, the traditional bamboo house stands as a model of practical and resilient design. Built on raised platforms, these homes are specifically designed to protect against both waterlogging and seismic activity. The choice of bamboo, known for its flexibility and abundance in the region, makes it the ideal material for such constructions.

Given that flooding is an annual occurrence in many areas, these houses are built with a higher plinth level, ensuring the living space remains above potential floodwaters. The walls are constructed using timber frames, with ikra panels—a resilient weed found in the river plains and lakes of Assam—embedded within them. These panels are then coated with three layers of mud mortar plaster, providing additional insulation and structural strength.

The design also emphasizes open spaces, with a front area known as the “chotal” and a back area called the “bari,” which serve as functional outdoor extensions of the home. These spaces not only offer ventilation but also contribute to the social and cultural practices of daily life.

In response to the region’s year-round rainfall, the houses are topped with gable or hip roofs, the most effective designs for preventing water accumulation. These roofs are constructed from locally sourced grass, which, despite the harsh climate, can last up to ten years before requiring replacement.

This thoughtful blend of locally sourced materials and context-specific design ensures that these bamboo houses are not only durable but also well-suited to the environmental challenges of the region. They represent a time-honored solution to sustainable living in harmony with nature.

c. Koti Banal, Uttarkashi

Although modern residences are often limited to two or three storys, the ancient koti banal structures of the Rajgarhi area in Uttarkashi tell a different story of architectural resilience. These earthquake-resistant buildings have stood firm for over 900 years, a testament to the ingenuity of traditional construction methods. Their design is as practical as it is enduring.

The lower levels serve as shelters for cattle, while the upper floors provide living spaces and storage for grains, reflecting the functional layering of the structure. The foundation is supported by a raised platform of dry masonry, ensuring stability. Access to the ground floor is through a single, small door, with smaller, south-facing windows providing light and ventilation.

One of the defining features of these buildings is the wooden balconies that wrap around the upper floors, cantilevered by wooden logs and safeguarded with wooden railings. The walls, which are 50 to 60 centimeters thick, are built using timber-reinforced stone masonry, bound together by a pulse-based mortar. The roof is a wooden framework covered with slate tiles, providing protection from the elements while maintaining the building’s traditional aesthetic.

Learn more: Advocating Sustainable Practices: India’s Ecologically Sensitive Regions

m. exploration

As we continue to explore the intersection of architecture, design, and sustainability, we invite you to delve deeper into the ideas and innovations presented on our website. Whether you’re looking for inspiring architectural projects, insightful videos, or detailed product information, Morphogenesis serves as a hub for thought-provoking content that reflects our commitment to responsible design.

If you still have unanswered questions about architecture and interior design, consider these additional resources for further information:

- Video gallery: Discover our latest projects and design philosophies through engaging visual narratives.

- Projects: Learn about our curated selection of residential, commercial, institutional, hospitality projects that embody Morphogenesis’ design philosophy – SOUL.

- m.blog: Dive into a wealth of knowledge with our blog, where we share insights on architecture, design trends, and sustainable practices.