Abstract: In this talk, Professor Nagendra examines the past, present, and future of nature in Bengaluru, one of India’s largest cities. Though threatened, nature in the city exhibits a remarkable tenacity. She charts changes in nature from the 6th century CE to the present, drawing on original social-ecological field research, coupled with archival analysis, satellite remote sensing, and oral histories. She concludes by exploring possible pathways to more sustainable and inclusive urban futures with a vision of a better future. Bengaluru is the story of a city where nature strives, yet thrives, providing insights on the prospects for urban sustainability in the era of global change.

Detailed Report

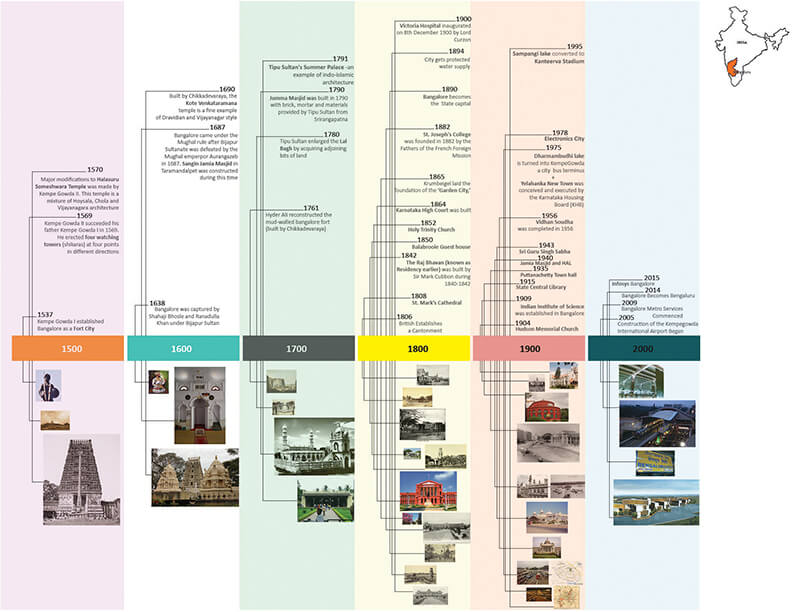

- Presentation starts with a beautiful poem written on Bengaluru in 1640s called “Shiva Bharat (1670)” by Poet.Parmanad explaining the vast landscape, Architecture, Flora and Fauna of the city while being ruled by Shahaji (Bijapur Sultanate) during the 17th century. This is the oldest document written on Bengaluru.

- What is the Present nature of Bengaluru as a city and how will it be in future?

- Three of the world’s 10 largest cities are in India: Delhi, Mumbai and Kolkata. Three of the world’s fastest growing cities are from also from India: Ghaziabad, Surat and Faridabad. It is estimated that 40 percent of India’s population will be living in its cities by 2030 and 50 percent by 2050. On another sobering note, 250 million more people are expected to be added to India’s urban areas in the next decade. So in this era of Anthropocene that humanity is believed to have created, where do so many people and their needs leave room for Nature? Is Nature something we need to even care about in our cities? How much do we know about urbanization of cities in 2050?

- Harini with her colleagues started to restore the Kaikondrahalli Lake in 2006, Valliyamma Layout, Sarjapur road, Bengaluru and restored around 100 species of birds.The question is all about – what kind of neighborhood do we want our children to grow up in?

- The approach within the research is not only to look at the biodiversity but also to look at all kinds of places and people within the city.

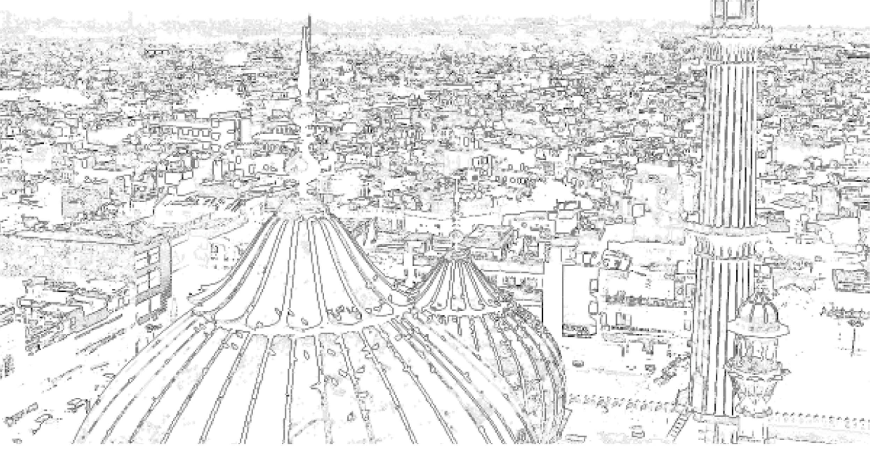

- Digital elevation model is used to understand the topography of the city. Entire city is divided in to the Malnad region (Thorny Cover, Jungle) – Western part of the city and the Maidan region (Grassy plains, fertile soil) – Eastern part of the city. These geographies determined the way people settled within the city.

- Inscriptions have been found 6 CE onwards on stones and copper plates which guide us through the settlement of people within the area.

- The Gangas, Cholas, Hoysalas and the Vijaynagara dynasty were the 4 dynasties that settled within the old territory. Most of their early settlements are found in the Maidan part of the city and eventually due to lack of space moved towards the Malnad

- Later, Kempegowda built the Market town under the influence of Vijaynagara dynasty.

- It is very important for any planner to know about these 2 important geographies of the city to reduce the climatic stress over the city.

- As you urbanize, you break the local cycle of use. Hence we end up importing water, food, energy from outside and vice-versa. This impacts the sustainability of the city.

- When the British came in to Bengaluru in 1840s, they started the Cantonment. Due to the semi-arid nature of the climate, they started large plantation across the city and collected a palette of species from Brazil, Madagascar, etc with the idea of seasonal blossoming, following the literature of Kalidasa.

- By 1888 there were around 1500 open community wells across the city to support the plantation and people. A lot of narrative also changes about the use of wells during that time.

- Under the British rule, the construction and reuse of lakes, at the same time increase in agricultural production was given a major thrust. By the later part of the 19th century, the British had succeeded in transforming the nature of the city. Large areas of the city and the cantonment that the British built away from the center of the city were lined with avenue trees on the roads providing shade to the travellers. Visitors remarked on the transformation of the city from a dry denuded landscape to one ‘completely hidden’ by dense grove of trees.

- Later, protection of nature happened through simplified view of nature. Simplification of biodiversity and social exclusion. Example of maintenance of Lakes for its various uses in different seasons.

- Urban Commons help in contributing the sense of a place. This eventually helps in creating a collective place for every community within the city.

The Speaker also brings to the fore some incredible people and movements from the least expected corners of the city very actively engaged in saving the last remaining fragments of nature from the clutches of concretisation and civic apathy. This is the hope, if we are to see a different better tomorrow.

Link to the presentation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xyZZiO8lZl4

Speakers Bio: Harini Nagendra

Harini Nagendra is a Professor of Sustainability at Azim Premji University, Bangalore, India. She is an ecologist who uses satellite remote sensing coupled with field studies of biodiversity, archival research, institutional analysis, and community interviews to examine the factors shaping the social-ecological sustainability of forests and cities in the south Asian context. She has conducted research and taught at multiple institutions, including most recently as a Hubert H Humphrey Distinguished Visiting Professor at Macalester College, Saint Paul, Minnesota. Prof. Nagendra received a 2013 Elinor Ostrom Senior Scholar award for her research and practice on issues of the urban commons, and a 2007 Cozzarelli Prize with Elinor Ostrom from the US National Academy of Sciences.