The discourse on sustainability in construction has long been subject to both genuine advancement and superficial adoption. As climate change accelerates, the role of buildings, which account for more than 40% of global carbon emissions, cannot be overstated.

To make matters worse, this is set to double by 2050 according to The Climate Group. The necessity for a substantive shift towards true sustainability in the built environment is beyond question. Yet, much of what is labeled as “green” today is diluted by greenwashing—a phenomenon where sustainability becomes a marketing device rather than a genuine endeavor.

Table of Content:

- The Role of Vernacular Architecture and Modern Technology

- Integrating Passive Design Strategies in Architecture

- Retrofitting Existing Buildings for a Sustainable Future

- The Imperative of Reducing Carbon Emissions

- Sustainability in Urban Design

- Redesigning Construction Practices for Sustainability

- The Way Forward

To move forward meaningfully, the built environment must embrace strategies that transcend token gestures and embody a long-term commitment to environmental stewardship. This shift is not merely about adjusting a few processes but about fundamentally rethinking how buildings are designed, constructed, and operated.

1. The Role of Vernacular Architecture and Modern Technology

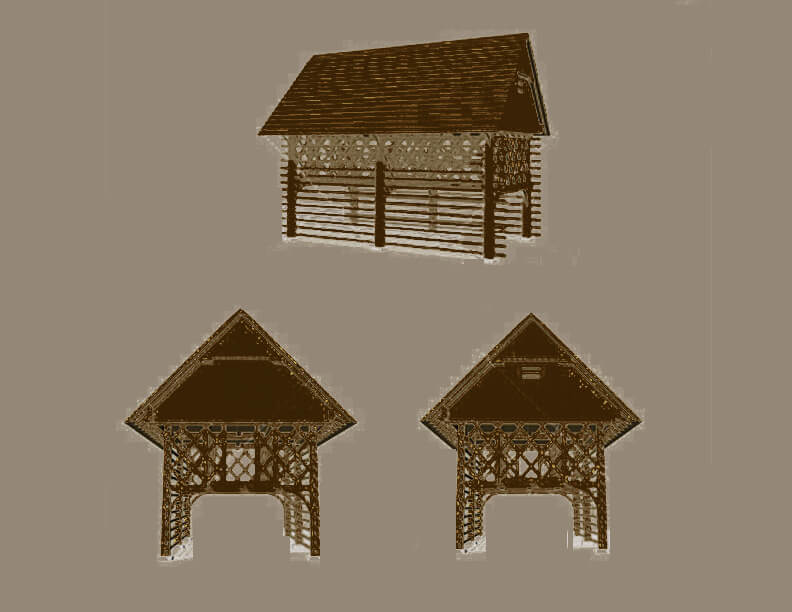

One of the most insightful paths to sustainability lies in the synthesis of vernacular architecture—which has historically aligned with the goal of designing spaces that best adapt to local climates by use of local materials. Traditional building methods, born out of necessity and resource efficiency, offer invaluable lessons for today’s architects and planners.

If we take the centuries-old structures in Morocco into consideration, where thick mud walls, shaded courtyards, and natural ventilation systems were not only practical but essential. These techniques, refined over generations, provide insights into how contemporary architecture can respond to local environments without the need for energy-intensive solutions.

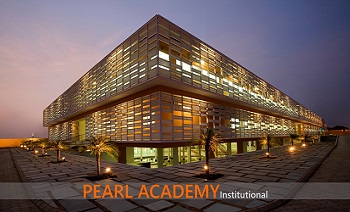

A prime example of how this fusion of the old and new can achieve sustainable results is seen in one of our institutional projects: The Pearl Academy of Fashion, Jaipur. The building design incorporates resource-efficient strategies, such as the use of local materials and vernacular architecture principles.

The incorporation of traditional building elements like Jaali (perforated screens), baolis (stepwells), and self-shading courtyards works in tandem with modern technology to create an energy-efficient, thermally stable structure. These strategies helped minimize the carbon footprint associated with transportation and manufacturing of construction materials.

The design also employs passive cooling techniques, earth sheltering, and evaporative cooling to achieve stable indoor temperatures without the use of air conditioning, even when external temperatures are much higher.

By blending these traditional techniques with modern advancements, such as smart energy management systems and advanced materials science, the Pearl Academy of Fashion exemplifies a pragmatic way forward. The key lies in recognizing that sustainability is not a new idea; it is one that has existed, in various forms, throughout human history.

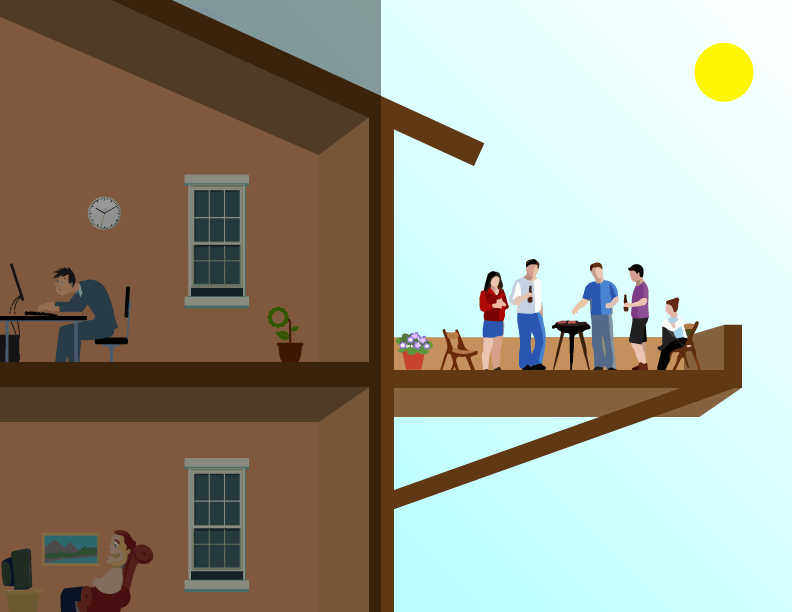

2. Integrating Passive Design Strategies in Architecture

A genuine commitment to green building practices involves adopting passive design principles and ensuring that these strategies are integrated from the very inception of a project. Buildings must be designed to work with their environments, not against them. This means prioritizing energy efficiency, using low-impact materials, and considering a building’s entire lifecycle from inception to demolition.

The practice of passive design—whereby a building’s form, orientation, and other features like natural ventilation, insulation, and shading reduce energy needs—has been a cornerstone of sustainable architecture for decades. While the theory is well understood, practical application, especially in urban and industrial contexts, often leaves much to be desired. Passive House standards, for example, have demonstrated the possibility of reducing a building’s energy consumption by up to 90%, yet they remain underutilized in global construction practices.

Our Delhi office, Morphogenesis 41, is the capital’s first USGBC LEED Platinum-certified commercial office building, embodying several of these design principles. The building incorporates passive design strategies to minimize energy consumption and environmental impact. It is oriented north to reduce solar heat gain, ensuring maximum daylight while preventing glare. The building’s envelope, with energy-efficient materials like AAC blocks and insulated roofs, minimizes heat transfer, reducing reliance on energy-intensive cooling systems.

Key features include a high-efficiency VRV HVAC system, which cuts energy costs by 25% compared to benchmarks, and water-saving measures like rainwater harvesting and efficient plumbing fixtures, reducing potable water demand by 47%. The use of low-impact, locally sourced materials, such as fly ash-based bricks and recycled content, ensures minimal environmental footprint.

These strategies are effectively realized in Morphogenesis 41, demonstrating how sustainable practices can be thoughtfully integrated into modern architecture to create energy-efficient, environmentally responsible, and comfortable spaces.

3. Retrofitting Existing Buildings for a Sustainable Future

While new buildings provide the opportunity for a fresh approach, the vast stock of existing structures presents a different challenge. Retrofitting older buildings to meet modern efficiency standards is an essential part of any serious sustainability effort. In fact, it is not an exaggeration to say that without large-scale retrofitting, the global effort to reduce emissions will be insufficient.

In cities like New York, forward-thinking policies such as Local Law 97 – a law that places emissions limits on individual buildings that are measured in carbon emissions per square foot – are beginning to address this issue. By mandating that buildings reduce their emissions or face significant penalties, this regulation demonstrates the feasibility of widespread retrofitting. The law aims to cut building emissions by 40% by 2030 and 80% by 2050, setting a precedent for other urban centers worldwide.

4. The Imperative of Reducing Carbon Emissions

The construction sector has been slow to address its carbon footprint adequately. The Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction underscores this, revealing that only 6% of energy consumed in buildings in 2022 was derived from renewable sources. This is starkly below the 18% target set by the International Energy Agency for 2030. The gap between current practices and what is required to mitigate climate change reflects the profound transformation still needed.

Buildings play a critical role in this transformation. If emissions from the sector are not curtailed, efforts to address climate change will fall short, and the consequences will be severe. More extreme weather events, rising sea levels, and widespread environmental degradation are already becoming increasingly visible.

5. Sustainability in Urban Design

The ambition for green buildings should not end at the structure itself. Sustainability must be an integral part of a city’s design and planning. Cities that foster walkability, public transportation, and green spaces are the ones that inherently reduce their carbon footprint. Yet, creating such environments requires long-term thinking and a shift in how we envision urban growth.

Consider Copenhagen, a city that has pledged to be carbon-neutral by 2025. Its urban planning incorporates green infrastructure, energy-efficient buildings, and a robust public transportation network, providing a model for sustainable urban living. This is not an isolated example but part of a broader movement toward cities designed with sustainability as a central tenet.

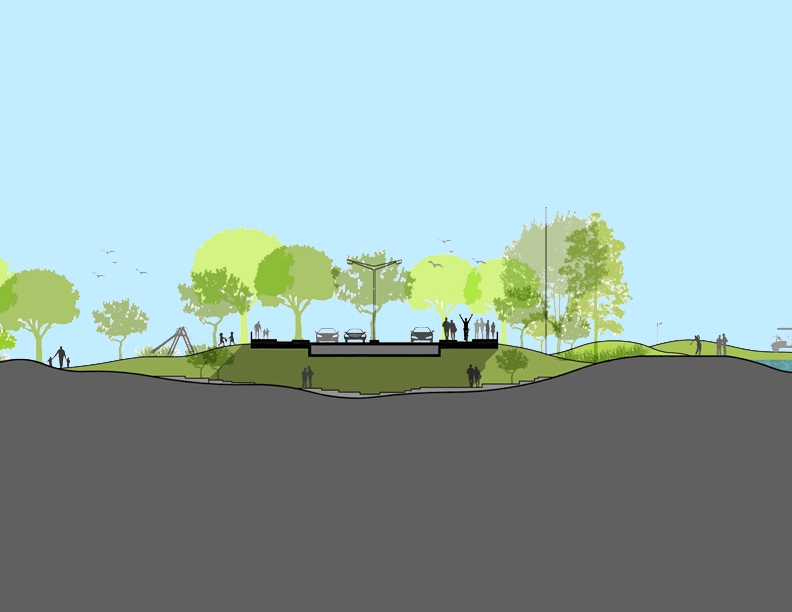

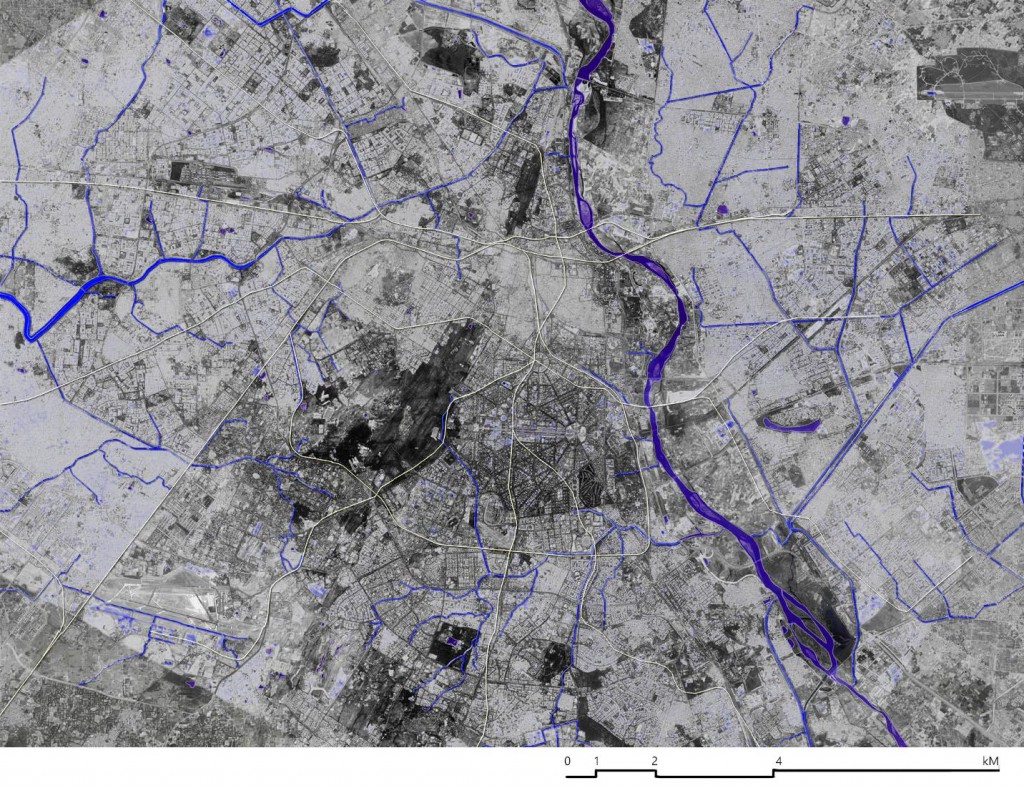

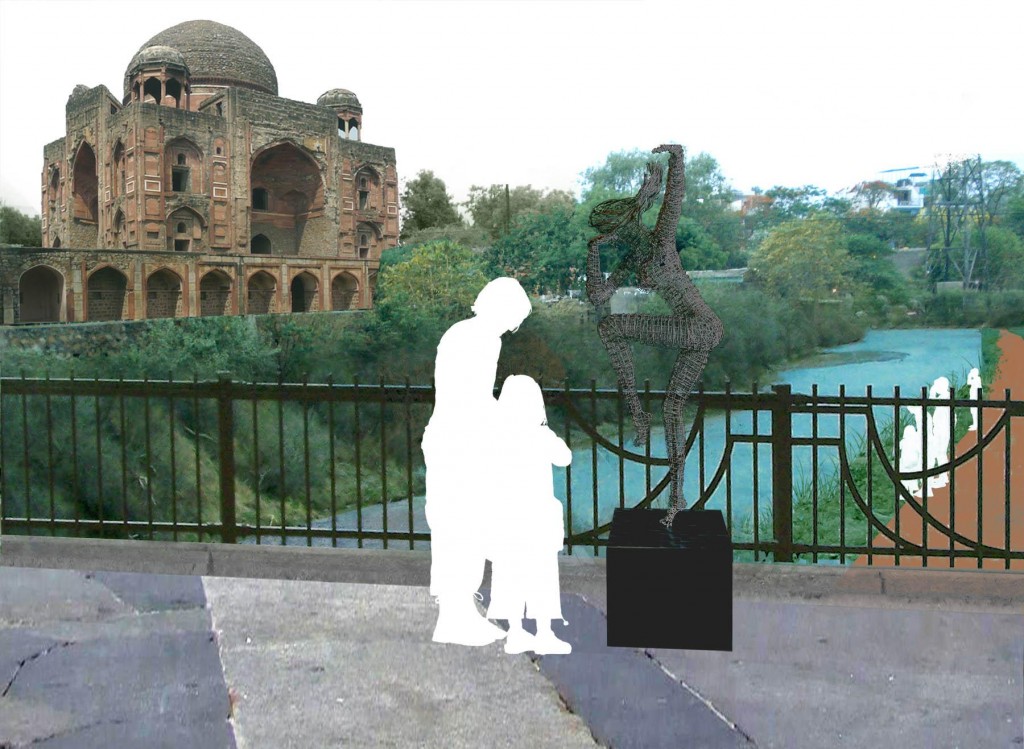

A notable example of this forward-thinking approach is seen in the proposal for the restoration of Delhi’s 350-kilometre nullah network. Historically, the nullahs functioned as essential watercourses, but over time, they deteriorated into unhygienic drains that contribute to pollution in the Yamuna River. Recognizing the value of these neglected waterways, this proposed initiative seeks to transform them into green corridors that not only address environmental challenges but also promote sustainable urban mobility.

The plan includes introducing walking and cycling paths along the nullah network, creating last-mile connections to public transport hubs like buses and metro stations. This integration would improve the effectiveness of Delhi’s public transport system while reducing the reliance on automobiles, fostering a more walkable and accessible city. Much like Copenhagen’s ambition to be carbon-neutral by 2025 through its focus on green infrastructure and public transport, this proposal envisions a holistic, sustainable approach to urban living.

The restoration effort also includes environmentally friendly strategies such as the use of organic reed beds and aerators to clean the water, rejuvenating the waterways in an affordable and eco-conscious manner. This could not only reduce pollution in the Yamuna River but also replenish aquifers and improve public health, offering a low-impact solution to several urban challenges.

Additionally, the nullah network is interwoven with Delhi’s rich historical and cultural heritage, with many significant sites located along its path.

By revitalizing these waterways, the proposal envisions creating new opportunities for tourism, sports, and other cultural activities, further connecting the city’s heritage with modern urban life. This initiative reflects a shift toward prioritizing sustainability and walkability in urban planning, offering a glimpse into a future where cities are designed with both environmental consciousness and community engagement at their core.

6. Redesigning Construction Practices for Sustainability

The construction phase has a significant impact on emissions. The energy required to produce, transport and apply the building materials, along with the environmental impact of heavy machinery, is often overlooked. A more thoughtful approach involves selecting low energy, locally sourced materials and designing buildings that minimize waste, both during construction and over a building’s lifecycle.

Moreover, closed-loop recycling systems ensure that materials are reused rather than discarded. These must become standard practice. The construction industry, in which environmental regularisations are yet to be implemented on a mass scale, has the opportunity to lead the transition towards a circular economy—where materials are continuously reused, reducing the demand for new resources.

Also Read: 15 Transformative Benefits of Green Building: Health, Economy, Social and Environmental

The Way Forward

To meet the challenges of climate change head-on, the construction industry must adopt a series of bold but achievable steps:

1. Implement Stricter Energy Standards: Governments and regulatory bodies must enforce higher energy performance standards for new builds as well as retrofits. In the current climate, the move towards net-zero energy buildings is not optional; it is a necessity.

2. Promote Retrofitting on a Global Scale: Retrofitting must be incentivized at a policy level to ensure older buildings meet modern sustainability standards. Without retrofitting, the global carbon reduction targets will be unachievable.

3. Incorporate Renewable Energy: Buildings should not just reduce energy consumption but actively generate energy through solar panels, wind turbines, and other renewable technologies.

4. Utilize Local Resources and Sustainable Materials: Reducing the carbon footprint of construction materials through the use of local, sustainable options will make a significant impact over time.

The road to mitigating climate change is fraught with challenges, but it is a road we must take. The construction industry is far from being a passive observer. With its impact on an urban scale, it has the potential to be at the forefront of global efforts to reduce emissions.

By embracing passive design principles, prioritizing energy efficiency, and integrating sustainability into urban planning, we can build a future where cities and buildings are not part of the problem but part of the solution. The time for incremental change has passed. What is required now is a fundamental rethinking of how we build, design, and live in our cities. The future of our planet depends on it.