It is common to see frequent headlines on plastic debris washed ashore and wilted sacrosanct flowers floating atop the rivers across our country. In a culture that holds its rivers in high esteem, it’s ironic to witness their transformation into polluted wastelands, betraying their reverence.

Namami Gange, a Morphogenesis initiative; Image credits: Morphogenesis

Studies state that a rise in population growth along our riverbanks is responsible for unusually high amounts of untreated and degrading waste going into the oceans. Out of the ten rivers that drain over 90% of the total plastic debris into the sea globally, there are three flowing through India – the Indus, Ganga and Brahmaputra. Besides these rivers and their tributaries, several other freshwater systems, and drains in India are neglected and have been investigated for the presence of untreated pollutants. What ultimately flows down the river results from a lot that happens outside the river. It is crucial to prioritise river conservation efforts by considering ecological, economic, technological, and social dimensions comprehensively.

How Indian Rivers Can Transform Regional Development

Dakshana Valley School

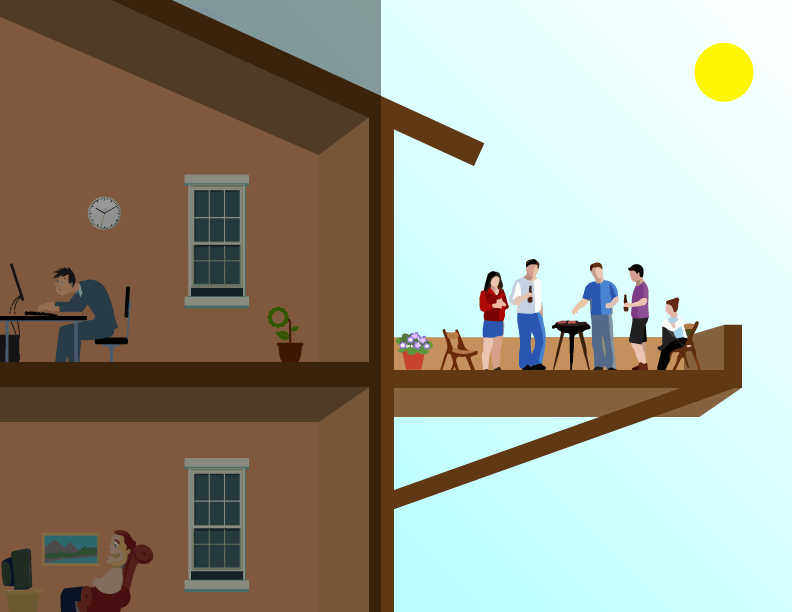

The preservation of natural lake at the Dakshana Valley School; Image credits: Anuj Joshi

Nestled in an idyllic valley surrounded by lakes and hills, in Pune, The Dakshana Valley School is envisioned as a home away from home. It is conceptualised as an educational hub that will impart technical knowledge and life skills to 2000 students. Here, students from marginalised communities will be imparted education as well as entrusted with responsibilities to build resilience and prepare for a better quality of life. The prime design motive was facilitating learning through engagement and respect for one of the most fundamental teachers in a child’s life: Nature.

Our design intervention focused on the preservation of existing man-made and seasonal water bodies onsite, as well as integrating buildings with the natural slope to facilitate rainwater flow. In addition, riparian plantations near the water bodies created a sustainable ecosystem, with plants grown at different elevations along the edge of the waterbody to reduce erosion and support local biodiversity. The natural lake becomes a social node for the students, and an appreciation for nature.

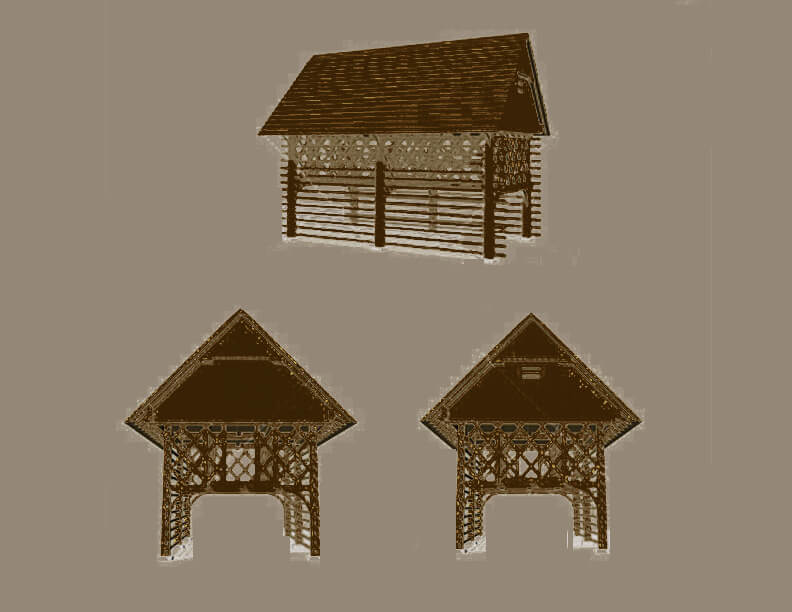

Delhi Nullahs

Delhi Nullahs is an example of a proposal undertaken by Morphogenesis in Delhi to revive the Yamuna River and its canals, locally known as nullahs. Once a water source, nullahs today are treated as unhygienic, polluted and breeding grounds for mosquitoes during monsoons.

The project proposal calls for an immediate end to the practice of slabbing over the nullahs. This is often done as a quick, clumsy method of hiding the filth from the nullahs. Instead, the nullahs are cleansed and disinfected, and existing land from the mostly dry riverbeds is recycled. To do this, natural filtration systems consisting of wetland organisms can be planted and localised sewage treatment plants installed at points where refuse enters the nullahs. These treated waters will replenish the natural Delhi groundwater levels as well as recharge the river.

Delhi Nullah project focused on the revival of watercourses within the capital city; Image credits: Morphogenesis

Small interventions can be placed throughout the city to create a contiguous, sustainable identity through the urban fabric. To connect these interventions and the various nullahs, old alleyways and service roads no longer in use, could be reclaimed and redesigned to act as pedestrian and cycle pathways. This network, hence, can be integrated with the existing transportation infrastructure as well as existing sites of social, cultural and natural historical heritage throughout the city. With the increased traffic and attention, these sites could become prime sources for water restoration and renewal.

Need for A Comprehensive Approach

For cities already struggling with water shortages, polluting a main water source is akin to throwing salt into a wound. So, is there a fix-it-all solution to our country’s unique river pollution issue? As stakeholders of the built environment, it is imperative to realise that the issues that our riverine systems face today are environmental, social, hydrological and infrastructural. A comprehensive approach is necessary to address the complex challenges facing our riverine systems.

Planting and growing native trees along water courses, aids in preventing pollutants and sediment from entering the river and stores millions of tons of climate-harming carbon. According to a study by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), approximately 30,000 hectares of land in the Ganges basin has been returned to the forest. The 2030 target is 135,000 hectares of land.

Involving local communities in the revitalisation efforts is crucial for the project’s success. Engaging stakeholders in decision-making processes, raising awareness about the importance of river conservation, and fostering a sense of ownership over the river and its resources can lead to greater long-term commitment and support to restore our rivers.